One day shortly before my father passed away almost 30 years ago, in late 1994 at age 86, he started talking to me about his brief career in politics back in the 1930s. It was an old story. My sisters and I knew bits and pieces. Dad had been a 30-year-old struggling lawyer in Brooklyn back then, had no background in politics, no money, the wrong personality (bookish and introverted like me), and no friends in high places. Still, he decided to throw his hat in the ring for the Democratic nomination for a seat in the New York State Assembly.

But there was always

something odd about the story. Dad

rarely talked about it, and what we knew had plenty of holes. Only one thing was crystal clear: After this experience, Dad came out with an

attitude. “All politicians are crooks. Every single one.” I still remember his tone of voice saying so. Even in the 1970s after I started working as

a young lawyer in Washington, D.C. on Capitol Hill, counting several

“household-name” Senators on the Committee where I served as staff counsel, including

politicians my parents mostly seemed to like.

Even then, I still remember Dad singing that same tune: “They are all

crooks. Every single one.”

Where did this attitude come from? We all have plenty of reasons to distrust politicians, especially my family living as we did in Albany, New York, with its then-famously crooked political machine. But Dad’s attitude was something deeper, more personal.

Brooklyn in the 1930s

Here’s what we knew. Dad first tried his luck in

politics in 1938, when corruption in big American cities was nothing new or

unexpected. Brooklyn, though, played in

its own special league. Bosses

controlled nominations and bristled at intruders. Graft and crime permeated the scene. My parents lived in a neighborhood called Crown

Heights at 1248 Saint Marks Avenue, barely a dozen blocks, an easy quick walk,

from the small candy story called Midnight Rose’s on Saratoga Avenue that then served

as headquarters for the notorious Murder Incorporated gang under the famous

mobsters Abe Reles and Albert Anastasio.

That set the tone.

But Dad was

idealistic and desperate. An immigrant,

he’d reached New York City as a five-year-old from Russia/Poland and grew up

poor even by Lower East Side standards.

He had worked his way through St. John’s Law School (class of 1928), attended

meetings of the Socialist-leaning Lawyers Guild, then earned his legal license

in October 1929, the month of the great Stock Crash. It was literally the toughest month of the

century to start a career.

Depression Era

lawyers struggled and starved. Dad

represented vagabonds, evicted families, then worked for a real estate

title company, but nothing substantial.

So with a wife, a one-year-old daughter (my big sister Honey), and

little else to lose, he decided to take a flier at politics.

Brooklyn back then

had twenty-three Assembly Districts, each electing one member to the State Legislature. These assembly seats were a big deal, prized

possessions: two-year terms, nice salary, status, and a platform for promotion,

a future judgeship, a seat in the State Senate, or maybe a partnership at a

good law firm. (And yes, plenty of graft

too if it suited you, but that’s not what this story is about, at least not

directly.)

Dad ran three

times for that Brooklyn Assembly seat, in 1938, 1940, and 1942. During that time, American entered World War

II, but Dad was too old for military service.

So he kept plugging away, at lawyering, raising a family, and

politics. He’d never win, but he kept

putting himself out there.

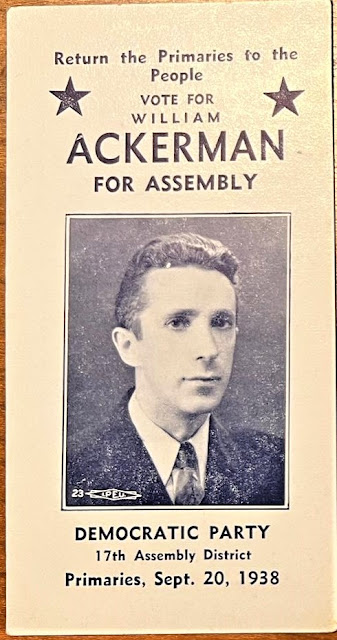

1938: The Good Race

But here’s the

thing. Of those three races, the only

one he ever talked about was the first, in 1938. Dad was proud of that campaign. That year, he ran a classic insurgent race. He did everything right: professional-looking

leaflets and handouts (all union printed, of course), neighborhood letters, speeches,

and organization. As his central

message, he railed against “Bosses” and corruption, claimed to be “the only

Democratic Candidate free from domination,” and told his voters to “take

control the primary system” and throw the bums out. He shook hands, made phone calls, walked

streets, and convinced neighbors to back him.

Should Kelly actually

win and become the new leader himself, the opportunities for Dad could be huge. Dad would suddenly become the favorite for that

Assembly seat nomination the next time around, or maybe something bigger.

But here the story

turned murky. Martin Kelly’s bid to replace

the incumbent leader of their Brooklyn Assembly District came to a head in April

1940 in a special primary election. The

incumbent was a former City Alderman named Stephen J. Carney, and Kelly lost

the vote. So up in smoke went Dad’s chances to ride Kelly’s coattails to bigger

fame. But then something else happened. There was a falling out, and Dad was left on

the short end of the stick.

1940: Not so Good

By the time Dad

launched his next campaigns for that same Assembly seat in 1940 and 1942, the mood

had changed. Dad never managed to last

in the race even until Election Day. Each

time, powerful people combined to block him, in ways Dad never really wanted to

talk about. All I knew was that, after

this experience, his attitude toward politicians had solidified. “They are all crooks,” he’d say with

first-hand authority. “Every one of

them.”

So what

happened? Shortly before he died in

1994, Dad gave me a clue. He left me

among his papers an old, tattered file folder labelled “Bill’s Political

Career” in hand-written ballpoint-pen letters.

I looked through the folder at the time, newspaper clippings, some letters,

hand-written notes, cards, but arranged chaotically and not shedding much

light. Too many missing pieces. So I just put it away with other old files where

it sat collecting dust as years and decades rolled by.

Along the way, I learned historical research, wrote a few books, including a book about New York City politics (yes, the one about Boss Tweed), and marveled at how new on-line digital technology was making it possible to open powerful new doors into the past. So when I happened to pull out that folder again not long ago – almost thirty years after I’d seen it the first time -- it occurred to me that now, today, with modern on-line research tools, I might have better luck.

I soon made

a new best friend: the now-digitized, searchable Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The Brooklyn Eagle had been one of the

best newspapers in America during its hay-day in the late 1800s and early

1900s, and it covered those local State Assembly races with loving care.

I soon discovered,

to my surprise, that my Dad had made a friend in the media.

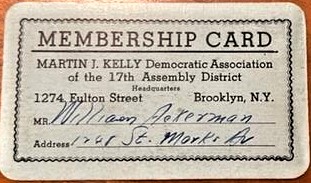

So

let’s pick up the story: Where we left

off, Martin Kelly, the insurgent lawyer who had taken Dad under his wing, finally

had his big moment. Kelly's chance to unseat the entrenched leader/boss of their Brooklyn Assembly district,

Stephen Carney, came in the primary election of April 1940. Kelly and Carney both fought hard and Dad got

very involved in the campaign. Kelly, in

his brochures, described Dad as the “independent assembly candidate of 1938”

and listed him as a major backer and coalition partner. Dad

But what about

Kelly’s followers, the more radical ones, the bitter-end true believers in “reform”? They were in no mood to make peace.

My Dad back in

1940 still fell into this latter category.

He had spent years railing against corrupt “Bosses” like Stephen Carney,

and he seemed genuinely surprised that his mentor, Martin Kelly, would make

peace with the enemy. So Dad decided to

stick it to both of them. That November,

there’d be an election for that same old Assembly seat again, with a primary in

September. Dad would stand on principle

and challenge Carney’s hand-picked candidate, a well-heeled incumbent named

Fred Morritt, even without help from a mentor like Martin Kelly. Dad would do it himself. Game on!!

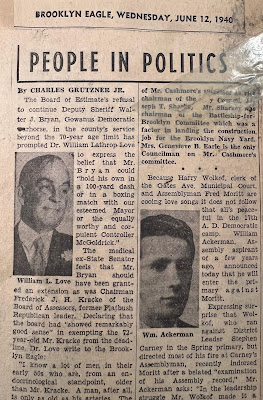

Grutzner, though

his “People in Politics” column, had been the first to disclose the peace deal

between Kelly and Carney. And when Dad decided

to break that deal by launching his own independent challenge for the State

Assembly, that was news! Grutzner featured

the story in his column, including a photo of Dad right there in the

paper. Then, as primary day approached, Grutzner

ran a second story about Dad’s campaign, this time quoting Dad at length blasting

the Carney-Kelly peace deal and asking disaffected Democrats to rally to

him. “My headquarters shall be at my

home, 1248 Saint Marks Ave.,” he quoted Dad as saying. “I ask all independent

Democrats, all those Democrats who desire real representation in the Assembly

and all those Democrats who love truth and justice, to communicate with me and

send me a word of confidence and support.”

This second article,

dated August 9, 1940, seemed to really irritate the now-unchallenged

leader/boss of that Assembly District in Brooklyn, Stephen Carney. Within

hours, Carney decided to act.

Dad received a message. Be it by

phone, telegram, or word of mouth, call it an invitation, a summons, a demand,

whatever you like, but before the day was out, Dad was required to appear at the

office of his nemesis, the boss Stephen Carney, and sit down for a meeting,

face to face.

The Private Meeting

Grutzner, the Brooklyn

Eagle reporter, learned immediately about the meeting and reported on it in

his column the next day – an article that was missing from Dad’s old file

folder. Bottom line: Dad was dropping

out of the contest. “William Ackerman

withdrew today from the 17th A.D. Assembly race, giving District

Leader Stephen J. Carney a perfect score in clearing primary hurdles out of the

path of his Assemblyman Fred Moritt.

The ink was hardly dry on Mr. Ackerman’s denunciation” of the

Carney-Kelly peace pact, Grutzner said, “when Mr. Carney sat down with Mr.

Ackerman for a long talk which resulted in the young lawyer’s

announcement.” Grutzner quoted Dad as

citing “Democratic unity in this important Presidential year” as his reason for

quitting the race.

Oh, to have been a

fly on the wall for that “long talk” between Stephen Carney and my Dad that day

in 1940! What actually happened behind

closed doors? On reading the Brooklyn

Eagle article, how I wished I still had Dad around to ask that question, or

even Mom who certainly would have known the bloody details. But neither of them ever mentioned it during

their lifetimes, so it probably wasn’t pretty.

What form of

arm-twisting did Carney use? Did he

shout and make threats? Did he use charm

and diplomacy? “Let’s be reasonable,” or

some nonsense like that? Did Carney perhaps

try to win Dad over as a new protégé? Or

did Dad try to win over Carney as a new mentor?

Maybe Carney promised Dad a fair shot at a primary for another job. Or maybe he promised something else. Who knows?

The only thing we

do know is the outcome. It was not friendly, and they didn’t pretend

otherwise. There was no good feeling. The bridge, if it ever existed, was

burned. When it was over, Dad simply delivered

the cold, terse message to the reporter, who announced it in the Brooklyn

Eagle, and that was that. Or was it?

1942: Unleash the Lawyers

All

of which brings us to 1942, when Dad again announced his candidacy for that

same damn seat in the New York State Assembly.

Why did he decide to run again?

Certainly, he knew he had no chance. He knew he’d made enemies. Was it pure stubbornness? Or perhaps finding out Carney had lied to

him, broken whatever promises he had made to get Dad out of the race in 1940?

Either

way, this time Leader Carney and his incumbent Assemblyman Moritt were not

amused. This time, instead of a polite

meeting, they decided to sic the lawyers on Dad.

Moritt, the Assemblyman

incumbent, promptly filed a lawsuit before a local Brooklyn Judge accusing Dad of

fraud. The legal complaint claimed that

Dad, in his nominating petitions, had included dozens of names that were faulty

or fraudulent, and demanded that Dad’s name be stricken from the ballot. Dad was incredulous. That corrupt pol, that conniving little wire-pulling

Boss, was accusing him of fraud!!?

My Dad could be accused of many things: stubbornness, bad judgment, the

list goes on. But fraud? My Dad was the kind of person who paid bills

within 24 hours and kept receipts for everything. Punctilious to a fault. Fraud?

The charge

horrified my Dad enough that he promptly filed a defamation lawsuit against

Moritt to protect his good name. He

demanded damages totaling $50,000, a huge sum of money back then. With no money to hire lawyers, Dad filed the

case himself, tapping out the complaint on his old Remington manual

typewriter. (I still have that antique

machine in my house.) In it, Dad called

Moritt’s accusations “wholly false” and intended for “the malicious purpose of

degrading and intimidating” him, to destroy his reputation and “scare” him out

of the race. I can easily imagine the

loud banging of the typewriter keys as Dad hammered out those words, trying to

avoid misspellings and typos in this age before computers, “white-out,” or

correction tape.

I don’t know what

ever became of that lawsuit. It probably

never got far; it’s not mentioned in any of the newspaper reports and, again,

he and Mom never mentioned it during their lifetimes. Nothing in the files. But the fix was in. A few weeks later, the Brooklyn judge issued

a ruling throwing out the nominating petitions for sixteen different insurgent

candidates fingered by Carney and other local Bosses, including Dad’s, removing

all of them from the primary ballot.

That’s how the Brooklyn machine did its dirty work in 1942.

So ended Dad’s

foray into the bare-knuckled world of New York City politics. He never won that Assembly seat nomination,

his mentor Martin Kelly never became district leader, and Dad walked away

feeling cynical about the whole mess. To

his credit, Dad had scared the Bosses into taking him seriously. In those second two races, 1940 and 1942, they

never beat him at the ballot box, but instead torpedoed him behind closed doors

and in a trumped-up lawsuit. That was an

education in political science you don’t get from a university.

A few years after

these events, Dad would take a competitive New York State civil service exam

and win a job in the New York State Attorney General’s office on his own

merits, with no nods from politicians.

This was the way he probably would have preferred it all along. The move finally brought our family to

Albany, the state capitol, where I was born in 1951. Working in the State Attorney General’s

office, Dad had the chance to play a key role in acquiring the land for building

the New York State Thruway, the Long Island Expressway, and other key highway

projects of the 1950s and 1960s.

Dad may have felt

defeated, even embarrassed, over the way the Brooklyn political bosses muscled

him out of his primary election campaigns in 1940 and 1942. It’s not the kind of story you like to share

with your kids over the dinner table. But

that’s how life works: People who stand

up to bullies often lose and get knocked down; people who get back up to try again

often just get knocked down again even harder.

But the fact is, Dad was lucky.

He won his battle. In the end, he

was able to walk away, reject a system that had lost his respect, and succeed

on his own terms. Ironically, even had

he won, Dad probably would have hated being a New York State Assemblyman. It hardly fit his stubborn personality, and

he probably would have grown just as cynical of politicians watching them work

up close and personal.

I’m glad I finally

managed to find the tougher side of the story that Dad tried to downplay all those

years. Telling the full version only makes

his stand against the Brooklyn politicians all the more admirable. Yes, they were crooks. And I’m glad my Dad was someone who took his

lumps trying to take one down and still managed to walk away.

No comments:

Post a Comment