Albany's long-time Mayor Erastus Corning with Democratic Party Chairman Dan O'Connell (with hat), circa 1970.

This story is complicated, so bear with me.

I was just a 20 year-old college kid when I got my first real bloody nose – figurative and almost very literal – in the political world. Welcome to Albany, New York, my hometown (scenic aerial photo above), back in the days of the Democratic machine, party boss Daniel P. O’Connell, and mayor-for-life Erastus Corning.

Getting the Politics Bug

I had just finished junior year that summer of 1972. I was living at home with my parents and had a dull summer job for the New York State government. Any excitement was welcome.

By then, I had gotten the political bug from attending a few anti-Vietnam war protests at school and had even volunteered to do grunt jobs in a few campaigns – including handing out leaflets on New York City street corners for unsuccessful 1970 NY Republican-Liberal Senate candidate Charles Goodell. (He’d end up losing to Conservative James Buckley, another learning experience.) Earlier, in high school, I’d joined my friend Bill Greenbaum to do after-school volunteer envelope stuffing for 1968 presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy.Luckily, that s

ummer of 1972 offered a new drama, the George McGovern campaign.

Who was George McGovern? Senator George McGovern (D-SD) would win the Democratic nomination that year only to lose in a landslide to Richard Nixon. But most people remember that campaign for the great scandal it produced, the Watergate burglary and cover-up, leading to Nixon’s 1974 impeachment and resignation. (I would later work in the Watergate Building for my law firm OFW Law, and McGovern would join our firm there, but that’s for another time.)

But for me, there was something more.

George McGovern’s 1972 campaign seemed miraculous at the time, a long-shot crusade by an unapologetic anti-war, anti-establishment liberal. McGovern faced enormous odds, but had won a surprising string of early primary victories. And one of the biggest, most important primary contests that year would be the one in New York State, whose 248 delegates could make or break his quest.

New York would hold its primary on Tuesday, June 20, just a few weeks after I’d come home from college, and the campaign had put out a call for volunteers. So off I went to sign up. My parents didn’t argue; they were happy just to get me out of the house.

The Albany Machine

Now about Albany, my hometown, allow me a quick word: Albany in 1972 had a special reputation. Since 1919, Albany had nurtured a local political machine among the most powerful and autocratic in the country. Our mayor, Erastus Corning, had already served 30 years in office, a tenure that would last over 40, a Guinness record.

But the real power, everyone knew, sat with Party Chairman Dan O’Connell and a handful of lieutenants, including two brothers named Charlie and Jimmy Ryan. Charlie and Jimmy Ryan both sat on the party executive committee, and Jimmy also served as Albany County Purchasing Agent. A state investigation in the early 1970s had uncovered payoffs and overcharges in his office of 500 percent or more, and stories of political strong-arm tactics, vote rigging, and the like were regular features in the local press.

Jimmy Ryan, it so happened, lived in our neighborhood, and was friends was my Dad. In fact, Jimmy was friends with everyone. That was his job. If anyone in his territory needed anything from the city or county, he made sure they got it. Jimmy also made sure they paid him back on Election Day. That was how political machines worked – that, plus the kickbacks, intimidation, vote-rigging, so on. (Please don’t act surprised. This isn’t new news.)Dan O’Connell, the party boss, already in his 80s, found little to like in George McGovern. Not that Dan was “liberal” or “conservative.” Dan’s Machine had delivered Albany’s votes for candidates of all stripes over the years. But what Dan resented most was outside interference. The great Albany writer William Kennedy, in his awesome history of my hometown called O Albany, explained:

In 1972 when the volunteer campaigners for George McGovern’s presidential candidacy were working miracles in primaries around the country, bringing out the student and youth vote, they descended on Albany, ready for another blitz, only to find Dan hostile to their plans. “I’m running the campaign with our own organization,” he said, “and we don’t want any separate campaign here.” The McGovern crowd persisted, and so Dan put himself on the primary ballot as the head of an uncommitted delegation; for Dan preferred Hubert Humphrey or Scoop Jackson [over McGovern].

And so the stage was set for a great head-to-head Primary Day contest: Dan O’Connell’s uncommitted slate versus the McGovernites. Dan had placed the machine’s prestige on the line. He was not going to lose.

Enter the Naive Young Volunteer

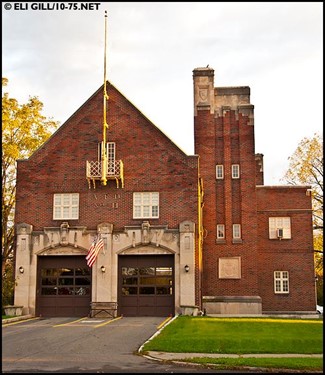

My assignment as a McGovern volunteer that day was to be a poll watcher at the polling place closest to my house, the firehouse on the corner of New Scotland Avenue and Maplewood Street. I knew the place well; it had a big field next to it where we kids had played touch football, and my Dad had taken me to see the big red firetrucks. I passed it almost every day walking to school or around the neighborhood. This was where people on our street had voted on Election Day for years.

I had never been to a voting place before. Just a few months earlier, late 1971, the national voting age had been lowered from 21 to 18, and I was still just 20, so this would be the first time kids my age could vote, let alone show up as poll watchers.

Why choose me for this job? I got my answer the night before Primary Day when the McGovern campaign pulled together all us young volunteers assigned to watch polls – about a dozen of us – for training. It was like preparing for battle.

A senior McGovern campaign staffer -- I don’t remember his name – told us they definitely expected the machine to cheat, and our job was to watch the voting and report anything suspicious. They’d have lawyers standing by to rush in and take charge. We junior volunteers would be the scouts, the messengers.

To prepare, they gave us a crash course on all the different, creative ways Albany pols had found over the years to cheat on Election Day with paper ballots or primitive voting machines. The list was endless: hiding pencil leads under a fingernail to invalidate ballots, placing vote machines at an open window to read them from the back, paying $5 per vote, so on. Then came our prime directive: Before reaching the polling place, we each needed to locate the nearest pay telephone booth (no cell phones back then), and make sure we had dimes and quarters in our pockets, to call in an emergency.

So on Primary Day, off I went to the firehouse with my credential letter from the campaign, for my first experience ever inside a polling place.

At the Firehouse

Inside the firehouse, in one of the garage bays usually occupied by an enormous red firetruck, they had set up a desk where the voting officials now sat with their list of registered voters and a pile of paper ballots. A voting booth was set up at a far end of the garage. No voting machines at the firehouse, just paper. People from the neighborhood came, lined up at the desk, gave their names, received a ballot, and could take it to the booth to fill out. Then they would place the ballot in a large wooden ballot box with a slot and an old-fashioned lock on top.

But then came the morning’s first surprise. Managing the polling place as chief voting official this morning was Jimmy Ryan himself, accompanied by two family members. I had never met Jimmy Ryan, though my Dad had mentioned him a few times. Jimmy was, after all, our ward representative. Jimmy had even helped my Dad get a summer job for me one year with the County.

To the McGovern lawyers, though, Jimmy Ryan was part of the enemy camp. So where did that put me? It did seem strange, this arrangement, that every voter, to receive a ballot, had to come face-to-face with Jimmy, a top lieutenant in the Democratic machine, whose leader, Dan O’Connell, had his name on the ballot. But that was how it was.

I remember introducing myself, showing Jimmy my credentials, and his politely leading me to a metal folding chair along the side of the firehouse where I could sit. Let’s be frank: Sitting down, I felt totally out of my depth. Being inside a polling place was utterly new and foreign to me. I had no idea what was normal. Jimmy and his co-inspectors were easily twice my age and experienced professionals.

I was on my own. All I could do for now was sit there and watch.

So that’s what I did. And here’s what I saw. For one thing, everyone was very chummy. Jimmy and his relatives, the voting inspectors, chatted up all the neighbors as they came to vote. But more, they also seemed to know something specific about each person. They raised it in a casual, friendly way. How does your son like his new job? How to you like the new sidewalk in front of your house? The new street lamp? Did the city fix that problem with your utility bill? Or your tax assessment? Or your court date? No pressure. Just asking.

Then I noticed something else. Most people in the neighborhood, after taking a ballot and talking with the Ryans, decided to skip the voting booth altogether. Why walk all the way to the back of the garage? They’d rather just mark their ballots right there at the front table. Sure, Jimmy Ryan could see it, but it was their free choice. No pressure. Just being friendly.

Sitting there in my poll-watcher seat, I fidgeted, cogitated. Was this a problem? Yes? Maybe no? As a first timer with no experience, self-conscious, afraid of looking silly, I continued to just watch.

Finally, after about an hour, I saw this: Two or three of the people coming to vote, after they got their ballots, made a point to walk with one of the Ryans over to a nearby firetruck. From where I sat, I could just see well enough to notice that, after the voter filled out his ballot, one of the Ryans would sign a paper and hand it to them. What was the paper? I had no idea. They seemed friendly. They laughed. Nobody acted out of place.

Asking A Question

But now I felt totally uncomfortable. That signed piece of paper, whatever it was, it had to be something. It couldn’t be nothing. But what could it possibly be? I tried to rationalize. There had to be some obvious, innocent explanation. But, racking my brain, I just couldn’t think of one. So, finally, getting up my courage, I decided I needed at least to ask a question.

I got up, walked over to Jimmy Ryan, got his attention, and, in probably the most timid, insecure voice he had ever heard, I said something like this: “Um, er, um, is he, um, actually allowed to do that?” Then I mentioned what I saw about the voters walking to the firetruck and receiving a signed paper.

Jimmy looked at me and, without hesitation, said the following: “You get the hell out of here!” That’s not all he said. There were more expletives. But that’s the part I remember, that and the loud voice.

I asked why, said I was a poll watcher just asking a question and had a right to be there. I showed him again my piece of paper. He looked at it and said: “You’re underage! You’re not 21.” I mentioned that the voting age had just been lowered to 18, but he said he didn’t care, or didn’t know, but “Get the hell out of here!”

One other small detail sticks in my memory: Right in the middle of this exchange, Jimmy’s face just inches away from mine, I noticed a sudden quizzical look in his eye. He was staring at my chin. A few days earlier, a doctor had removed a small growth there and left some stitches, one apparently sticking out, out of place. Without hesitation, Jimmy absent-mindedly reached and tugged it off, like straightening my collar so I would look OK, like a parent or uncle would do. An instant later, he was back to business.

Calling for Backup

Fortunately, I remembered my training from the night before. Rule One: Don’t argue! Instead, if an argument breaks out, leave immediately, go to the phone booth, call the office, and get help.

So that’s what I did. I said “OK” or something like that. Then I left, walked over to the phone booth down the street, dialed the McGovern campaign, and told them what just happened. But rather than being alarmed, they sounded happy. “Wait outside in front of the firehouse,” they told me. Help was on the way.

I waited there and, within about ten minutes, a caravan of three large cars pulled up, including lawyers from the McGovern campaign, lawyers from the New York State Attorney General’s office, and a news crew from Channel 6, WRGB, one of our three local TV stations. The lawyers had been waiting all day for the chance to pounce on an actual case of voting fraud. So too the TV news. Here was their chance.

They quickly found me, heard my quick explanation, then the lawyers ran ahead to the firehouse, leaving me behind. Things got confusing. There was shouting, pushing, arguing. I remember a fist fight between one of the Ryans and one of the lawyers, wild punches thrown back and forth, bloody faces. In the process, a table was knocked over, a wooden ballot box fell on the concrete and cracked opened, dozens of white ballots flying in the air as frantic voting inspectors ran after them.

Minutes later, I was standing in front of the Channel 6 TV camera, someone holding a microphone, Jimmy Ryan standing at one side holding one of my arms, a McGovern lawyer holding the other. I had only been on TV once before in my entire life at that point, for a local kid’s show called The Freddie Freihofer Show when I was three years old. All I remember of the interview now was this: Once the camera started, they barely allowed me to get in a single word. Instead, Jimmy Ryan and the McGovern lawyer each broke in, tugging me back and forth as they spoke, each insisting he was my best friend. I remember Jimmy dominating the interview, explaining it was all nothing, just a misunderstanding about the confusing new rules for the 18 year-old vote.

So it went for about an hour, the lawyers haggling, inspecting any scraps of paper they could find, looking for evidence, while Jimmy and his inspectors kept collecting the vote.

My Dad Shows Up

Finally, after things had barely calmed down, my Dad came over to vote. He had not heard yet about the trouble. When he arrived, Jimmy Ryan went up to him and told him. They pulled me aside. Jimmy patted me on the shoulder, said I was OK, just doing what I was supposed to, sticking up for my side. No hard feelings.

Sure enough, my Dad, no fan of McGovern, voted the machine ticket and make no secret of it.

That night, Channel 6 TV News carried a short piece about the incident at the firehouse. They flashed a quick image of me standing between Jimmy Ryan and the McGovern lawyer, then couched the whole story simply as confusion over the new 18-year-old voting law. No mention of any cheating. Nor did the State Attorney General lawyers ever bring charges. I asked one of them about the mysterious signed papers I’d seen being handed to voters by the firetruck, and he said they were probably tax documents, but he couldn’t prove it.

Dan O’Connell’s ticket won by a mile. George McGovern carried New York State, a key victory on his road to the Democratic nomination, winning 230 of the 248 delegates up for grabs. But not the ones from Albany County.

Like most things growing up, it took years before I really understood what I had seen that day at the Albany firehouse. In 1973, I would move to Washington, D.C. to start law school, and soon start working for a U.S. Senator named Charles H. Percy (R-Ill), a liberal Republican who carried a special grudge against another local Democratic political machine, the one in Chicago. Seemed like a perfect fit.

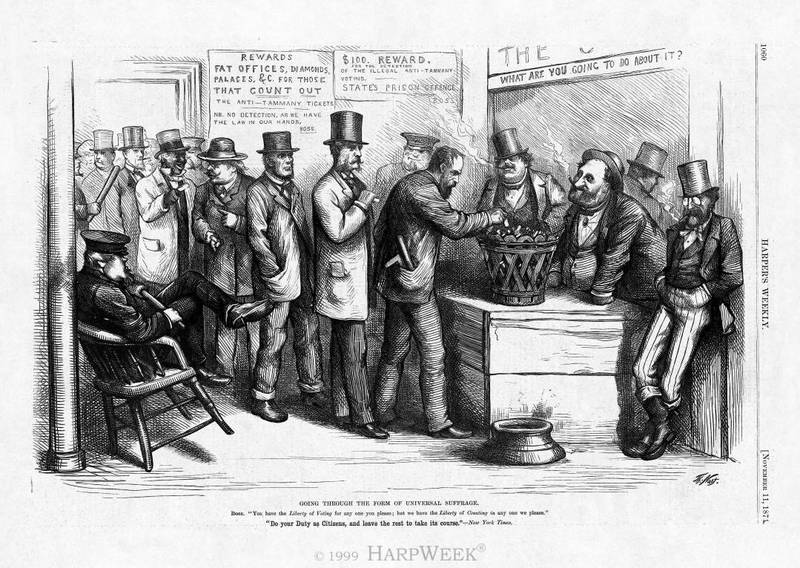

Later, of course, I would develop a fascination with New York City’s Tammany Hall, the biggest, baddest political machine of all, and its leading light, Boss William M. Tweed. It all seemed familiar. I’d even write a book about him called BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol Who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York. Check it out on Amazon or Audible.

The old O’Connell machine is long gone in Albany. Dan O’Connell himself died in 1977 at 91 years old. After his death, Charlie Ryan would lose a power struggle to Mayor Corning, who would continue as Mayor until his own death in May 1983, a total of 41 years in office. The Corning-Ryan power struggle would become grist for a 2019 off-Broadway play called The True. According to William Kennedy’s book, Jimmy Ryan would die in Florida in 1979 after an illness.

I was no hero that day at the firehouse in 1972, just a nervous, tongue-tied, inexperienced kid trying not to screw up my morning as a campaign volunteer. But the cheating was just so flagrant that even a first timer like me couldn’t fail to spot it. And it didn’t take a big, fancy speech to make the point – just a simple question, a phone call, then letting the chips fall where they may.

But was Jimmy Ryan really a villain? Sure, there was corruption back then. Famously so! But, for a politico like him, his main job was to do favors, make government deliver for people in his neighborhood. All he and the machine demanded back was loyalty. A fair bargain? Not perfect. The corruption and strong-arm tactics not helpful, nor even necessary.

As for his throwing me out of the firehouse that day in 1972, it’s hard to hold a grudge. Bluster aside, he was just doing his job that day too, trying not to screw up his morning delivering the vote for his maestro Dan O’Connell and the machine. Politics was and remains a team sport. You need people who can block and tackle. They made the wheels turn for Boss Tweed in the 1870s, for Dan O’Connell in the 1970s, and plenty in between, including plenty of good guys. In those couple of hours, Jimmy Ryan taught me more about politics, the real-life, street-level kind, than I could have learned from years of college courses or Capitol Hill seminars. For that I thank him.

No comments:

Post a Comment